A common misconception when discussing the armored vehicles of Warsaw Pact countries is that they were either only manufactured in Russia or that the production of licensed versions or indigenous armor models was only permitted under Soviet supervision.

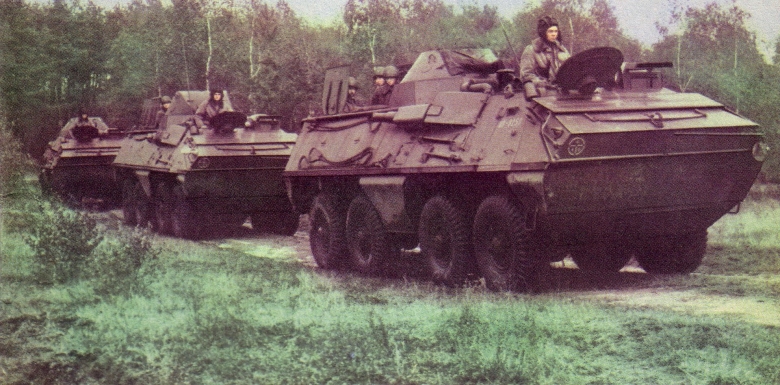

SKOT-2AP

Actually, the Warsaw Pact countries had a large degree of autonomy in this matter (with the exception of major strategic decisions, such as letting Czechoslovakia manufacture BMP-1s for the entire Pact). This autonomy was often used to build indigenous armored vehicles for the Pact. The downside, however, was that it led to numerous squabbles and disagreements between countries that usually had to be resolved on a political level, causing a certain degree of friction.

One of the key factors behind the Polish refusal to co-manufacture the BMP-1 with Czechoslovakia was their experience of cooperating on the OT-64 APC in the early 1960s. Today, we’ll take a look at that experience.

The Start of Cooperation

In our previous article, we discussed the early history of the OT-64's development. Several prototypes of the OT-64 were built between 1958 and 1960 and despite numerous teething problems, Czechoslovakia had a working prototype of an excellent APC with a futuristic design that was ready for mass-production by 1960.

OT-64 SKOT

The first mention of specific cooperation between Czechoslovakia and Poland regarding production of the OT-64 dates back to an August 1960 meeting of the Czechoslovak-Polish Economic Cooperation Committee in Warsaw. Another meeting took place in Prague in January-February 1961 and this resulted in a memorandum describing their intent to work together.

In March 1961, the Polish delegation sent a memo to the Czechoslovak Ministry of Defense regarding improvements to the vehicle. At roughly the same time, both Czechoslovakia and Poland sent their delegates to Moscow where they had the chance to see the new Soviet BTR-60P prototype. Based on this experience, Poland proposed to instead produce the BTR-60P in both Czechoslovakia and Poland, because, during the planned comparative trials that would take place in 1962, the Soviet vehicle proved better than the Czechoslovak one.

With this one act, they managed to:

- Seriously annoy the Soviets who saw this as yet another Poland versus Czechoslovakia squabble they'd have to resolve, as early post-war arguments were still fresh in their memory; despite being formal allies against "capitalism", Poland was not very happy with some regions that were, in their view, historically Polish. Meanwhile, the Czechoslovaks had not forgotten the eagerness shown by Polish forces in annexing parts of Czechoslovakia before the war. Soviet military advisors also expressed doubt over whether Poland would even be capable of producing the BTR-60P in large numbers.

- Infuriate the Czechoslovaks because the OT-64 used a large number of parts produced for other vehicles and introducing a completely new design would mean significant delays. Industry representatives also claimed that considering how different the Soviet design was from anything produced in Czechoslovakia so far, it would be simply impossible to start producing those vehicles within any reasonable time frame.

The negotiations dragged on until July. At one point, Czechoslovakia officially began to consider cancelling the coordination with Poland. However, in the end, the Polish changed their minds after a joint meeting of Soviet, Polish and Czechoslovak representatives that took place in Moscow in July 1961.

Manufacture Planning

Disputes about production did not end there. The initial plan envisaged a first production run starting in 1964 with 8,600 vehicles built between 1964 and 1968 – 4,000 for the Czechoslovaks and 4,600 for the Polish. That was all well and good, except that the yearly deliveries Czechoslovakia proposed counted on production of 2,000 vehicles per year, 1,200 of which would go to Czechoslovakia and 800 to Poland. This annoyed Poland due to the clear preference of Czechoslovakia and an agreement on the actual production numbers was only reached much later on.

SKOT-2A

Another source of arguments was the extent of production distribution. In October 1961, it was agreed that the engines, transmission and suspension were to be produced in Czechoslovakia, while the hulls, wiring and final assembly was to take place in Poland. The Czechoslovak company AZ Letňany was selected as the "main developer" of the vehicle and no changes to the design were to be made without its approval. In addition, Czechoslovak representatives were to be present at each step of the vehicle's assembly in Poland.

The mutual animosity and delays caused by the prolonged negotiations had severe consequences. In order to start production on time, the Czechoslovak manufacturers received a special exemption from the quality assurance process and this led to a high number of complaints about quality from the Polish.

Furthermore, complicated agreements between the two countries caused certain areas of the part manufacturing process to become a major waste of effort. For example, to produce armor plates for the vehicle:

- the raw plates were rolled in Vítkovice Ironworks (Czechoslovakia)

- the plates were transported to Poland for processing

- processed plates were transported back to Czechoslovakia (PPS Detva) for hardening

- hardened plates were transported back to Poland for assembly

and so on. In addition to quality complaints, the entire process turned into a logistical nightmare. These issues, along with other political decisions, such as the 1963 Czechoslovakia military budget cuts, meant production was not only delayed but the total number of ordered vehicles was also reduced.

Conclusion

Despite all the aforementioned manufacturing issues, as well as other problems, production did start successfully and it ran until 1971 with a total of 6021 vehicles built. Unfortunately, it would be beyond the scope of this article to describe all the issues, but one example included the Polish keeping secret the fact that the armored plates processed in Poland were prone to cracking and delivering a number of defective vehicles to Czechoslovakia before the problem was discovered.

Two SKOT-2A and one SKOT-2AP

The vehicle's development did not come cheap, with total costs climbing to 33 million CZK and over 1.1 million man-hours between 1958 and 1963 and reaching 57 million CZK by 1965. With the work to prepare for production, the total cost climbed to 139 million CZK. For Poland, preparation costs for the mass production were allegedly as high as 620 million (Zloty), although Czechoslovakia disputed that claim. Price calculations were actually a very complicated process anyway – for example, the Czechoslovaks estimated the total cost of the raw materials used to build one vehicle at 4143 rubles, while the Polish put the same costs at 8097 rubles, only to be reduced to 2227 rubles later. These miscalculations only underlined the general atmosphere of mistrust between the two countries.

A scathing 1966 Czechoslovak military report about the OT-64's production efficiency claimed that the cooperative agreement between Poland and Czechoslovakia was quite unfavorable towards Czechoslovakia and recommended no further "international cooperation" attempts take place in such programs unless far better conditions were offered by the partner. The Czechoslovak opinion on the Polish military industry of the time could be summed up in an excerpt from the said report:

“We can conclude that this cooperation was nothing but a certain form of an economic help for Poland, allowing it to build a solid industrial branch that didn't exist before it...”

While partially justified, these sentiments (expressed openly by certain members of the Czechoslovak military), along with the Polish participation in the Soviet 1968 "Intervention", tainted the relationship between Poland and its southern neighbor for years to come.

Sources:

- M.Burian, J.Dítě, M.Dubánek – OT-64 SKOT

- M.Dubánek – Trnitá cesta k zadání úkolu SKOT

- M.Dubánek – Od Bodáku po Tryskáče: Nedokončené československé zbrojní projekty 1945-1955

- Author's own archive collection