Commanders!

Earlier, we discussed the first of the features that are coming in Update 0.29 and, today, we’d like to take a look at another one. The upcoming season will not feature a progression vehicle line – instead, it will focus on gameplay improvements, bug fixes and mechanics overhauls. That does not mean, however, that it will be entirely devoid of new vehicles – today, we’d like to tell you about the one that will be obtainable via the season-spanning Contract system, replacing the K1A1 – the ZUBR PSP.

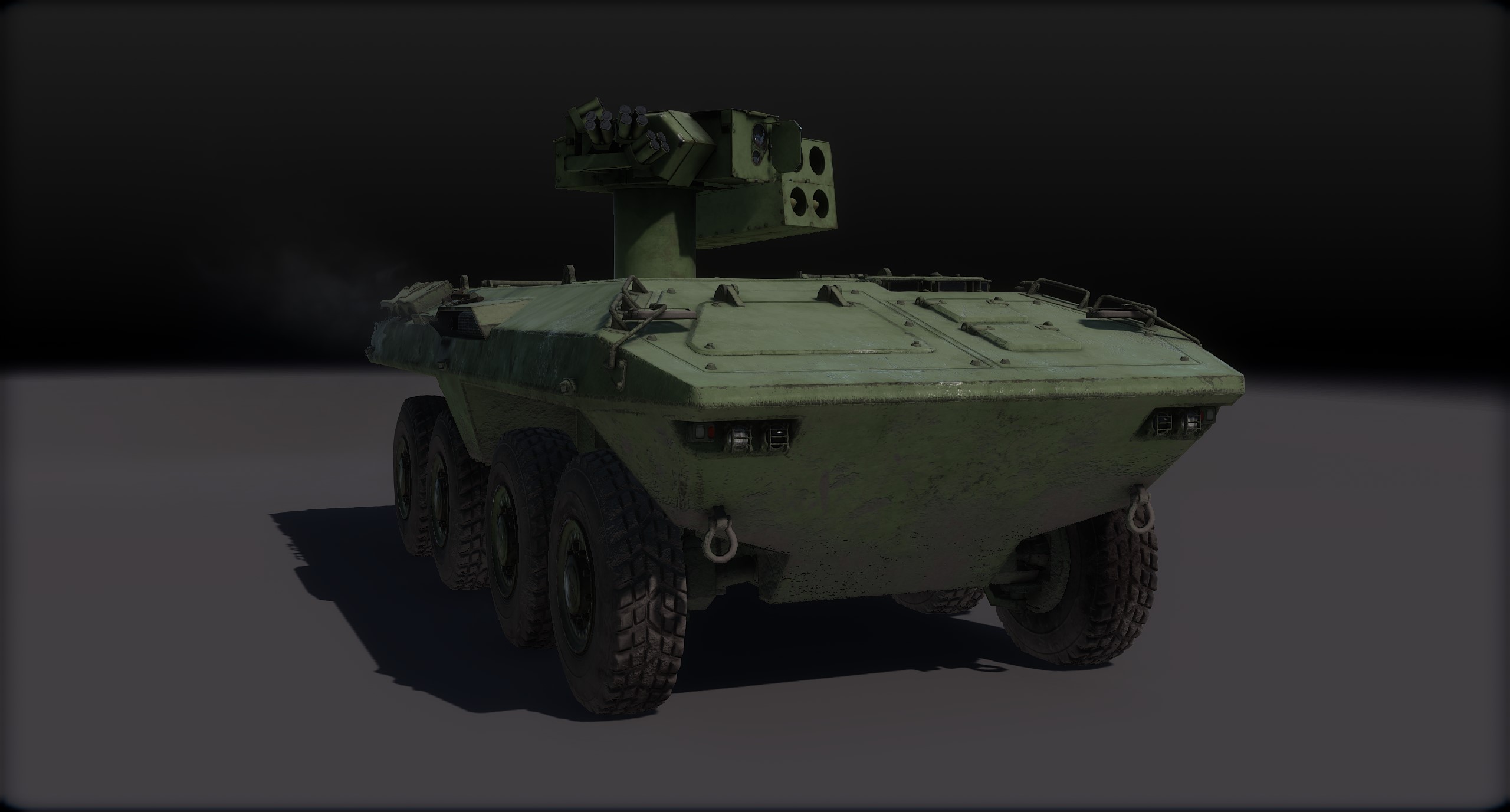

ZUBR PSP model

Never heard of this vehicle? Don’t worry – few have. It never won any battles or even entered service, remaining a footnote in the history of AFV development. It was, however, an interesting design that nicely demonstrated the problems and dilemmas faced by the industry of the countries belonging to the Warsaw Pact after its dissolution.

To understand the state of things the Czech, Slovak, Polish and many companies found themselves in, one must look at what happened between the 1960s and the 1980s in former Czechoslovakia. After the war, the country was reborn only to immediately fall under the Soviet influence.

The country traditionally had a strong industrial base and military industry was no exception. After all, in 1934 and 1935, Czechoslovakia was the biggest arms exporter in the world (its share was 27 percent of all arms sales). The war changed a lot of things but not the industrialized nature of the country. What did, however, change was the location of the industry. After the war, fearing a conflict with the western powers and the fact that the traditional industrial cities such as Pilsen and Prague were well within the reach of the U.S. Air Force heavy bombers, the communist regime had the entire heavy armor production moved to Slovakia, specifically (mostly) to the city of Martin.

The region had previously never been heavily industrialized and this step brought a sharp living conditions increase to the area along with thousands of jobs. What followed was a lengthy adjusting period but by the early 1960s, the ZTS Martin Company started to really pick up steam, churning out hundreds of tanks per year.

The 1960s and the 1970s are now known as the “good old days”. On top of re-arming the Czechoslovak army itself as well as most of the Warsaw Pact (few Warsaw Pact countries were able to produce armor in sufficient quality and quantity), the weapons were exported en-masse, mostly to the Middle Eastern Arab countries. The Arab-Israeli swallowed hundreds of Czechoslovak-made vehicles that needed replacing the demand for Czechoslovak armor was so high that, in fact, the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (that handled the export factor) were often fighting over any produced vehicles. In some cases, the military actually had to return some old, mothballed vehicles to service simply because the modern ones were all sold abroad and, despite its lofty communist proclamations, the country really needed that cold, hard, western cash.

Destroyed Czechoslovak-made T-34 tanks, Mitla Pass, 1967

Of course, not everyone had western cash. The massive Arab purchases were often either subsidized by Soviet loans, paid for in natural resources or, sometimes, not paid for at all. But that didn’t really matter to the state-run economy that, in the era of computerization, still used pre-war indicators such as steel production to measure success. In any case, the arms production of the 1970s was profitable, but not nearly as profitable as many think. For such a small country, it was quite a feat, but it came at a terrible cost.

In the 1970s, Czechoslovakia was producing approximately 800-850 tanks every year, most of them for export. But, like we mentioned, these weren’t really exported anywhere profitable and it was clear the situation could not last forever. Around 85 percent of these vehicles went to the other Warsaw Pact countries – but these were in the same situation as the Czechoslovak army and were not paying even for the production costs. Between 1981 and 1985, the Warsaw Pact countries received approximately 3.7 thousand armored vehicles at a loss of 1.24 billion crowns. During the same period, exports of the same vehicles to non-socialist countries generated the profit of 2.34 billion crowns.

To demonstrate just how incredibly unsustainable this model was, let us compare the current situation with the pre-1989 one.

In 2018, President Donald Trump demanded the NATO countries to spend 4 percent of their Gross Domestic Product value on defense. This demand was met with outrage as many of the NATO countries currently spend considerably less. Poland, for example, spends 2 percent of its GDP, France spends 1.8 percent and Germany spends approximately 1.2 percent.

In 1987, Czechoslovakia was spending 19.94 percent of GDP on its military. Almost twenty percent – let that sink in. In 1989, the Czechoslovak army had 4585 tanks and 4900 IFVs. Today, the Czech army has around 30 active tanks with an unknown number of obsolete T-72s mothballed. The other Warsaw Pact armies were in roughly the same situation with their militaries completely disproportionate to their actual populations. This was paid for by the taxpayers – after all, the laws of economy work regardless of political regime and, in the end, someone has to foot the bill. As the economy situation (and, therefore, living conditions) worsened due to the abysmal results inherent to socialism, people started to revolt and, ultimately, it all came crashing down in 1989 – relatively peacefully, for the most part. The end of the Soviet Union came soon after.

Naturally, one of the first things for the new government to do was to reduce the outrageous military spending. This happened all across the Warsaw Pact that was formally dissolved in 1991. What this meant for the companies producing military hardware was:

- They instantly lost 85 percent of their markets

- The reduction of the Warsaw Pact armies along with the “fire sale” that followed the breakup of the Soviet Union meant that the market would be saturated for years with entire divisions’ worth of hardware being available basically for scrap metal prices

- Even after the worst passed, the former Warsaw Pact clients were interested in western hardware to get closer to the NATO, not more Soviet export models

The remaining 15 percent was also a massive problem. Apart from the abovementioned situation, by the 1980s, the traditional Middle Eastern clients stopped paying for shipments altogether as their economy situation worsened. The biggest post-1989 contract – some T-72M/M1 260 tanks for Syria – was the swan song of the Slovak tank-building industry. Many of the Syrian Civil War tanks you see today rolling around have “Made in Czechoslovakia” stamped on their hulls.

ZUBR PSP hull mock-up, IDET 1997

What followed were waves of company closures (by 1989, more than 90 thousand Czechoslovaks were involved in the military industry). The 1990s left many people extremely bitter and gave birth to the myth that the Czechoslovak industry was “given away” to the westerners by traitors. The reality is, of course, much more complex than that because it is true that some assets were privatized in an extremely suspicious manner – but that is not for this article to describe.

The important part is that this branch of industry nearly collapsed – and those companies that survived (Tatra, Aero Vodochody etc.) did so at the cost of incredibly high subsidies from the government – their debts were, once again, footed by the taxpayer. This didn’t concern just the big producers – building an armored vehicle requires a complicated logistics chain of companies that were hit just as hard. One of them was a company called Přerovské strojírny.

The original company was actually founded in Přerov in the 1850s as a producer of various types of machinery (mostly related to agriculture) and complex components such as transmissions and it remained in private hands until it was nationalized and merged with a newly built machining plant in Přerov starting from 1948. During the communism era, it produced various heavy machinery components as well as heavy vehicle parts and by the end of the 1980s, like many other such companies, struggled to keep its doors open. In 1990, it was transformed from a state-owned company to a joint stock one, was privatized and, once again, transformed into a holding called PSP with various sub-companies emerging from 1994 onwards.

One of these daughter companies was called PSP Bohemia a.s. – it was founded in 1995 as an arms trading sub-division of the PSP holding. With their experience in heavy machinery, its owners wanted to take a shot at filling the vacuum left by the more traditional armored vehicle producers. In the mid-1990s, the newly transformed Czech Army was beginning to look for a replacement of the obsolete OT-64 wheeled APC. Something western of course, with a good protection level – the world had moved on from the idea of massive Soviet BMP formations pouring through the Fulda Gap.

As it happened, the PSP holding had very good contacts in Italy, apparently due to the fact that some of the components from Přerov made it to Iveco and Fiat even before 1989 (Italy, regarded as a more pro-socialist country than others, had above-average relations with Czechoslovakia).

What apparently happened was this – PSP Bohemia got their hands on the blueprints of some Freccia components (Freccia is the AFV counterpart to the Centauro), specifically the suspension and the hull. They used some of these to produce a proposal for an AFV family they named ZUBR.

This was actually a very unique situation for the 1990s. Most of the “traditional” armor producers focused on upgrading the Soviet tech (a typical example being the T-72 Moderna upgrade series by VOP 027 Trenčín), few had the balls to offer something entirely new.

The ZUBR PSP series consisted of a modular 6x6 or 8x8 chassis that could be fitted with various turrets and other combat modules in order to fit a wide variety of roles, including:

- Armored Personnel Carrier

- Infantry Fighting Vehicle

- Fire Support Vehicle

- Missile-based tank destroyer

- Anti-Aircraft launcher

- Armored ambulance

- Engineering vehicle

And several others. The parameters of each vehicle differed but the weight could reach up to 20 tons. The vehicles had a crew of three, their position depending on the vehicle’s configuration.

The armor of ZUBR was fully configurable – the hull would be made of welded steel, offering protection against small arms only. However, additional plating could be installed, increasing the protection levels up to STANAG 4569 Level 4 (Soviet 14.5mm AP bullets at 200 meters). Some sources claim the protection could be even heavier. A lot of emphasis was put on anti-mine protection as well – this would, in fact, become this vehicle’s unique selling point.

Additional systems would include:

- Automated fire extinguishing (0.6 second reaction time)

- NBC filter system

- Run-flat tires with automated pressure system

The vehicle would be powered by an engine of customer’s choosing, although the variant that was talked about the most was the Cummins ISX 15 liter 500-600hp (depending on tuning, the most common value listed being 516hp) inline 6-cylinder turbocharged diesel engine paired with an Allison transmission, allowing the vehicle to go as fast as 115 km/h. The ZUBR was also designed as fully amphibious.

The suspension was the really interesting part. The drawings and promotions materials show something akin to the Freccia one (with hydraulic shock absorbers protruding from the hull) but it’s unclear whether the PSP holding would be able to produce it. Instead, it’s possible the vehicle would be using the patented Tatra suspension system that allowed even heavy vehicles to drive through places others could not, making it truly world-famous. All axles were powered, potentially allowing for some extreme off-road capabilities.

The weapon system, of course, depended on the vehicle’s configuration. The hull was designed to be as modular as possible – multiple existing weapon systems were considered for it, including the commercial Cockerill series of turrets or the Italian HITFIST line.

Compared to the obvious money grabs (projects likely intended to siphon development money off the military budget) such the relatively recently unveiled Zetor Wolfdog IFV, the project was generally well-developed and competently put together. Drawings do allegedly still exist, as do small-scale models. A full scale mock-up was unveiled during the 1997 IDET expo in Brno and continued to be formally available until 2003, but, as it happened, the whole project ran afoul of politics.

A small digression first, though. One thing that might not be obvious at first glance is that arms deals are often not about vehicle quality – they are about purchasing or selling influence and good will. That’s why some rather unpleasant (but usually oil-rich) countries spend vast amounts of money on purchasing a lot of tech from multiple different large sources such as the United States, Great Britain, France etc. at the same time, resulting in their militaries being armed with a wild assortment of (often incompatible) tech.

The same thing was, to a smaller degree – but still, happening in the Czech Republic of the 1990s and the early 2000s, resulting in one of the best known corruption affairs in Czech history – the purchase of Austrian Steyr Pandur II IFVs that were purchased for a very high price following several rounds of bribes, resulting in an investigation that eventually saw a single lobbyist being jailed for four years. To this day, the word Pandur is practically synonymous with corruption in the Czech Republic.

As is probably clear from the paragraph above, the ZUBR PSP vehicle family never stood a chance. The company that offered it, Bohemia PSP, was, however, brought down by another contract, investing a lot of money into a co-operation with the Ukrainian Kharkov plant and building the T-72MP prototype as a competitor to the T-72M4CZ for a major upgrade of the Czech tank forces. This too went nowhere and, lacking the cash to continue this endeavor, the PSP holding let its daughter company go broke. PSP Bohemia filed for bankruptcy for the first time in 1999 and was eventually officially dissolved in 2003.

But, as they say, all’s well that ends well. The PSP holding did not go broke with this adventure – in fact, today, it produces more machinery than ever and as for the Czech arms export – the last years have seen an unprecedented rise thanks to the activities of the Excalibur Army company and the Czechoslovak Group holding it is a part of. Some even claim the “good old days” are back – but that is a story for another time.

In Armored Warfare, the ZUBR PSP will be a Tier 7 Premium Tank Destroyer. As its hull shape suggests, it will share more than one similarity with the other Tier 7 TD, the Centauro 105 – but, unlike its Italian counterpart, it will have the option to use two very different configurations.

But before we proceed – please note that the values below are designated as Work in Progress and will most likely change during the balancing phase of this vehicle’s introduction. With that in mind:

The first configuration will be the Gun Tank Destroyer variant with a Cockerill CT-CV turret similar to the one the Tier 8 105mm Wilk uses, turning it into one of the deadliest vehicles of its Tier. Even though the turret will not feature a Ready Rack, the high accuracy of the 105mm gun paired with the ability to fire deadly HESH shells will make sure that this vehicle will be fully capable of ruining the day of anything it encounters on the battlefield. Compared to the Centauro, this vehicle will have:

- Higher damage per shot, accuracy and damage per minute values despite the absence of a Ready Rack (500 damage, 530mm of penetration for the APFSDS shell, 4.5s reload time and 0.066 accuracy)

- Better gun depression and elevation (-10/+42 degrees)

- Somewhat thinner armor, compensated by the presence of an unmanned turret

- Roughly the same mobility (20 tons, 516hp engine, maximum speed of 115 km/h)

- Lower camouflage but higher view range, lower camouflage penalty per shot

The second configuration will be that of a Missile Tank Destroyer. With it selected, the vehicle will have a four-tube TOW launcher instead of the abovementioned gun turret, making it a direct competition to the NM142 TD. Like the NM142, the ZUBR PSP will be able to fire top-down attack missiles – with one major difference. The TOW missiles the ZUBR will use will be older models with worse performance, compensating for the ability to have four of them ready to launch instead of just two:

- BGM-71C TOW (760 damage, 630mm of penetration)

- BGM-71F TOW-2B (top-down attack, 350 damage and 200mm of penetration)

The system will be capable of launching one missile per 2.5 seconds with the reload time per missile being 5.5 seconds (22 seconds for the full magazine).

As the abovementioned mobility numbers suggest, the ZUBR platform will be considerably faster than the NM142, but, as a wheeled vehicle, more difficult to control and, as a larger vehicle, less stealthy (although its view range will be higher).

And last but not least, the owners of this vehicle will be able to choose one of the three following Active Abilities:

- Sharpshooter (temporary bonus to accuracy, rate of fire and camouflage compensated by the fact that the vehicle cannot move while this ability is active)

- Silent Running (temporary bonus to stealth at the cost of mobility, plus firing breaks the effect)

- Engine Overdrive (temporary bonus to mobility at the cost of camouflage)

All in all, this vehicle will be two rather distinctive ones packed in one neat package. Whether you choose to use the missile variant or the gun one, we hope that you will enjoy it.

See you on the battlefield!